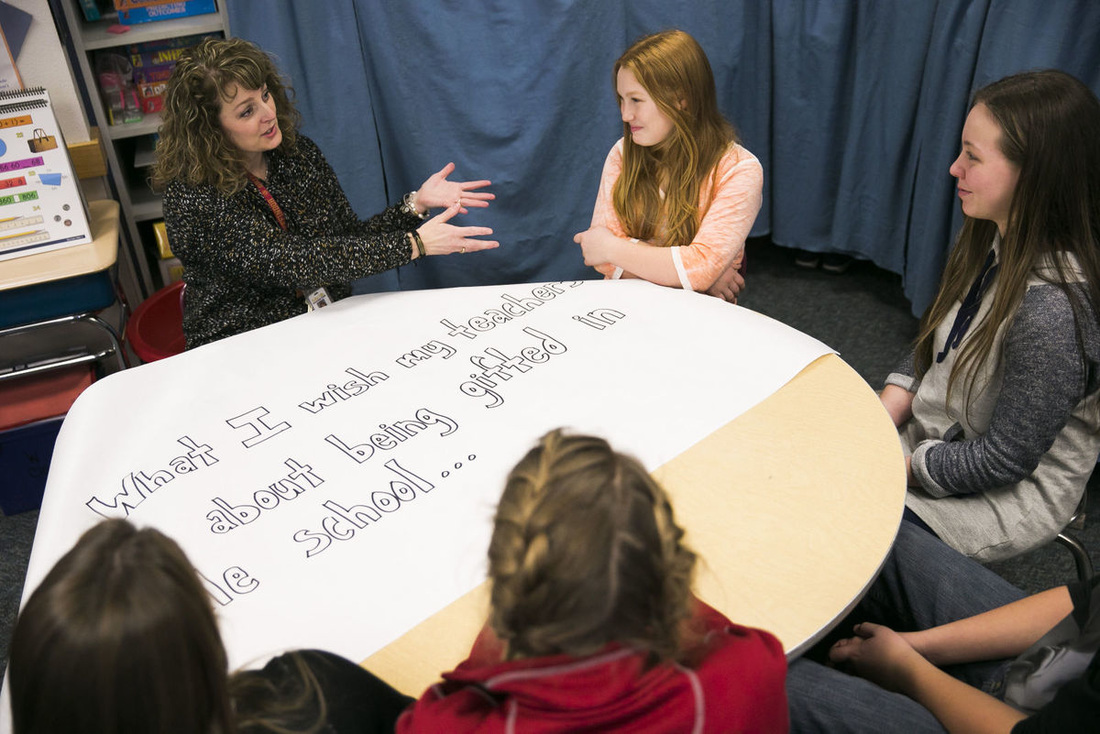

The Yakima Herald Republic published a piece in January 2016 about area gifted programs. See the full article here.

What’s In a Name? NCLB vs. ESSA Wendy Clark WAETAG Board Member Spring 2016 Although I speak a comfortable amount of Spanish, I don’t think of myself as bilingual. That was, until I considered my acquired second language of Teacher-Ease. If your vocabulary is filled with acronyms like IEP, TPEP, OSPI, GT, and SBAC you know what I mean. Recently in the world of education we replaced one acronym for another. No Child Left Behind (NCLB) was, in effect, left behind to become Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), also referred to as the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). But what does this mean for those of us in the field of gifted education? Is it yet another policy that could result in the focus being even further removed from our highest-achieving students? Alas, no! Not only was the JAVITS grant retained but, for the first time, ESSA/ESEA was also written to include several provisions for gifted and talented students. These provisions come from the TALENT Act (S.363/H.R. 2960), a lengthier acronym which stands for To Aid Gifted and Talented Learners by Empowering the Nation’s Teachers. This legislation recognizes that in order for success in the 21st century, there are numerous fields that need high levels of talent. It also states that our top students are not performing at internationally competitive levels. Importantly, it addresses the serious imbalance of students of color or from poverty being included in the percentage of top students. Not only does it address needs for students currently performing at high levels, but also those with the potential and ability to become high achievers. This is such promising news for those of us that have long been advocating for the needs of ALL gifted and talented students, rather than those that seem to fit a stereotypical mold. According to the Fordham Report, in the era of NCLB the highest achieving students made only minimal gains, while also receiving some of the lowest levels of attention from their teachers. “Were Congress to accept teachers’ views about what it means to create a “just” education system—i.e., one that challenges all students to fulfill their potential, rather than just focus on raising the performance of students who have been “left behind”—then the next version of NCLB would be dramatically different than today’s.” (Fordham, 2008) It appears somebody was listening. The TALENT Act, introduced these four key emphases:

Encouragingly, the support mentioned above also comes with avenues for possible funding. Title I funds may be used to identify and serve gifted and talented students, while Title II funds may be used to provide professional development in the area of gifted education. All districts and states will be required to include the advanced level students as a subgroup in their reports for achievement data. Additionally, districts applying for Title II funds must include information as to how the learning needs will be met for gifted and talented students. Both Washingtons (state and D.C.) seem to agree. We have decreed that highly capable services are part of basic education. Similarly, ESSA specifically states that the needs of “all students” include the gifted and talented. So, what’s in a name? When the WASL became the MSP, those of us in the classroom didn’t feel like there was much of a difference. Had we simply swapped one assessment for another that looks and feels the same? Will the same be true for NCLB vs. ESSA? I think not. This seemingly small name change comes with exciting and promising aspects for our best and brightest. I encourage all advocates for gifted and talented students to learn more about how these changes, set to start taking effect in the 2016-2017 school year, will improve our abilities to meet our students’ unique needs. For more information, go to www.NAGC.org High-achieving students in the era of NCLB. (2008). Washington, D.C.: Thomas B. Fordham Institute.  Teach Them Early- EASY ≠ SMART By Wendy Clark WAETAG Board Member With the end of another year upon us, I think ahead to the coming fall when I will undoubtedly have the same conversation with several of my new third grade families. They are concerned. Their child is upset that school is too hard, perhaps the teacher doesn’t like them. They don’t understand. In past years, their child enjoyed school even though sometimes it was too boring. They are worried. Will their smart child dislike school and not reach their potential? My end of the conversation usually goes something like this. “I understand why you’re concerned. Your child is very capable and so far in school most things have come quite easily, possibly too easily. I’m trying to meet their needs by providing work at their level, which may be higher than their grade level’s standards. It’s important for your child to work through these new challenges and learn now that EASY does not equal SMART.” At this last comment, I get mixed reactions. While many recognize the need for a mindset that welcomes challenge and hard work, some don’t agree that eight-year-olds should be expected to work through difficult tasks that challenge their abilities, no matter how far above grade level their abilities lie. Understandably, the majority of the K-2 years are spent learning the most technical aspects of reading, that letters make sounds that translate into words. It is extremely important that we spend much energy getting students to learn how to read in K-2 so that they can more easily transition from learning to read, to reading to learn. So, what happens with students that come to school knowing how to read? The same can be wondered about the ability to compute and decompose multi-digit numbers, or write sophisticated stories. If we’re not careful about the kind of feedback and praise we give students, students may end up thinking that they must be so smart because things come easily to them. What happens then when they come upon a challenge? As analogies go, once young kids think that "easy = smart", then it isn't a huge leap for them to feel that "hard = dumb". How do we prevent or fix this kind of thinking? We need to be careful with our praise and focus on the effort put forth. This will help to develop a growth mindset as opposed to a fixed one. Carol Dweck, a Stanford University psychologist, has published a lot of research in this area. People with a fixed mindset believe that their intelligence and talents are static and may not spend time trying to develop them. Years of praising students for tasks that require little to no effort may inadvertently help lead them to a fixed mindset, and keep them from attempting challenging tasks that put them at risk of failure. By recognizing the high intelligence and talents in our gifted students early, and providing encouragement and praise for efforts during difficulties, we can help them to develop resiliency. To not only persevere through challenges, but to also seek them out in order to foster capabilities is a worthy goal for all students. Hard work does matter, and students need to develop grit. However, having either a fixed or a growth mindset won’t make anyone more or less gifted. This article, published in Psychology Today, shows that while hard work may trump talent, that’s only the case if talent doesn’t also work hard. In small districts like mine where the basis of our highly capable program in the early grades is clustering students with teachers that have had some training in the area of giftedness, it is essential that teachers learn to foster a growth mindset. Clustered students are in general education classrooms where it may be easy for them to get the message that putting forth little effort will result in the highest grades, rewards, or praise. Simply measuring their work against the grade level standards or bell curve of the class isn’t enough. We need to keep them challenged, recognizing attempts and failures as opportunities to help them develop a growth mindset. This video by Northwest Gifted Child Association is a fabulous example of how students that don’t experience challenge in their early elementary years don’t learn how to learn and develop grit. This often leads to underachievement and fear of failure when they are older. Carol Dweck has outlined four steps to help develop grit and move from a fixed to a growth mindset. You can read about them here. These steps can help students recognize and talk back to negative, fixed mindset thoughts. Using this kind of metacognition, students then begin to take action and seek opportunities for growth. Gifted students need to know and understand their giftedness, to recognize that their unique traits and strengths. Teach them early. Yes, many tasks may still come easier to them because they are smart or talented, but when the going gets tough the easy:smart::hard:dumb analogy will no longer hold them back. For more on this topic: How Not to Talk to Your Kids Living and Creating: Fear is Not a Disease The Power of Belief – Mindset and Success Making a Difference: Motivating Gifted Students Who Are Not Achieving |

Wendy Lee ClarkTeacher and advocate for gifted and talented children of all ages. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed